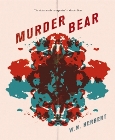

reviewed by Harry Giles

Face Your Inevitable Ursine Doom

Murder Bear is a brutally nihilistic romp through poetic and popular history: a big-hearted, big-brained murder spree that cares deeply for its readers even while confronting them with their inevitable ursine doom. In Murder Bear everyone has a good time and learns a great deal about the fleeting nature of existence, often by dying horribly.

Murder Bear enters those moments when we are naked and alone, has no sympathy, and kills us

This little limited-edition pamphlet comes quick after Herbert's compendius double-volume Omnesia (Bloodaxe, “alternative text” and “remix”), and offers many of the same pleasures as his extensive back catalogue: tongue-twisting language and unapologetic punning, paired with unpretentious intellectual investigation and wide-ranging exploration. But Murder Bear stands out for its concentrated nastiness: it has one mission, accomplished with a quick poetic knifing, which is to remind us that we will all die at the hands of Murder Bear. In case you need clarification, Herbet gives us A Night Story:

Once upon a time there was a Murder Bear. Then he killed everyone. The End.

This is really all you need to know about Murder Bear. Herbert allows us some time for sympathetic self-reflection, as when in Dear Reader he writes “You never saw a bear so alone”, as long as we accept that we're going to die. He allows us to be impressed by his skill in multiple poetic forms, for the pamphlet includes neat examples of a sonnet, a sestina, hendecasyllabic verse and more, as long as we accept that no amount of poetic mastery will save us from being eviscerated by a bear. He allows us to enjoy his many, many puns (“mourning / as their dictionaries burned, 'I like a corpse / in cuneiform'” being my personal favourite) as long as we accept that our laughter is just a prelude to the screaming. Again, for clarification:

'You can beat him, though, can't you?' I thought I'd explained that there really is no hope. Now go to sleep.

This is nihlism in its purest form. Herbert, via Murder Bear, kills everything and everyone, from cartoon characters to French essayists. The nihilism is used as a vehicle for satire, as when Bear Grills Bear Grylls, condemning “ephemerons and mumble-newses” who “learnt to rue that urge to interview”, or when the excesses of Christmas are skewered:

Always drunks to be nudged off station platforms, little match girls to sauté by flame-thrower, snowmen needing to eat their magic top hats, anxious mothers who must see all their trimmings, lazy fathers who need a shot of buckshot. – Hendecakillabics for the Restive Season

However, the nihilism is ultimately not snobbish or self-aggrandising, because Herbert knows that he too is going to get murdered. Herbert sees our excesses, mocks them, then shrugs and looks to his own. The innocent die too, or perhaps no-one is innocent: the match girls die alongside the drunks.

Similarly, while Herbert packs his work with intertextual reference and surprisingly intellectual punning, there's never the sense that this is to get one over on the reader. Herbert never hides his references in vagueness: he plunks them out for all to see. I did not at first know that The Passionate Psychobear To His Love was a reference to a Marlowe poem and madrigal, but it was easy enough to find it (look it up yourself) and now I can't stop singing it. There is a lot of googling and flicking through dictionaries of quotations involved in reading Herbert's poetry, but there's so much fun happening and so much simple linguistic pleasure to be had that this never seems excessive, obscurantist or patronising.

The completeness and violence of Murder Bear is, however, frightening: there is genuine horror in the pamphlet. Nihilism is like that. When Murder Bear, dressed in the skin of a flayed victim, on Christmas night whispered “I hear you when you're weeping...” I shivered, aware of my own meaningless doom and the absence of true comfort. I laughed, too, but nervously, as we do at movie gore splatter. Like all the best monsters, Murder Bear enters those moments when we are naked and alone, has no sympathy, and kills us.

Such nihilism is under-explored territory for poetry, which is often spoken of as a means of solace, or survival, or joy. All the better, then, that the pamphlet should explore it with such vim. In Herbert we have a wry and trusted Virgil to guide us through the horror. Deeply committed to entertaining his readers and to fulfilling the promise of language, there is no poet from whom I'd rather hear my death sentence.

Harry Giles grew up in Orkney and now lives in Edinburgh. In 2010 he founded Inky Fingers, a spoken word events series which he continues to help run. He has given feature performances at nights, including Chill Pill, Jibba Jabba and Last Monday at Rio, won multiple slams including the UK Student Slam (2008), the BBC Scotland Slam (2009), the Glasgow Slam (2010), and been published in journals including Magma, PANK and Clinic. He makes theatre as well as poetry; recent projects include What We Owe (The Arches, October 2012), This is not a riot (Crisis Art Festival, July 2012) and Class Act (Ovalhouse, May 2012). His pamphlet, Visa Wedding, was published in November 2012 by Stewed Rhubarb Press.