reviewed by Anthony Adler

The Deniable Mystique of Silver Birch Trees

Ambivalence is a cruelly underestimated word. To be ambivalent is not necessarily to be uninterested or indifferent, nor to possess only meagre opinions such that one cannot make up one’s mind. I am not in the throes of a lukewarm indecision: I am in the grip of a passionate ambivalence, between a rock and a hard place, between the devil and the deep blue sea – or at least between liking Midwest Ritual Burning really quite a lot in parts, and finding it terribly disappointing in others. This is an awkward predicament for anyone attempting to write a review. Whenever I start with well-deserved praise, I feel that I’m whitewashing my discomfort; whenever I consider the opposite, I pull back: despite my reservations and aversions, something about this collection has made itself at home in the back of my skull. Morgan Harlow must be doing something very right.

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this dilemma is by looking at the first poem, ‘Gorilla Dreams’:

You were in studio number six at the university humanities building when someone unlocked a wooden horse head containing Michelangelo’s tools for shaping stone. On a table the body anesthetized: T.S. Eliot. A drawing with empty space, a herd of mice, and in the distance, a giraffe where one expected a cat. Apricot colours. Suddenly A– worried over the last survivors. Outside over an angular white concrete façade, the night sky.

There are a lot of things about this poem that I don’t like. It’s a dream poem, and I don’t like dream poems as a rule: the inscrutability of dream-logic is an open door for lazy, unearned mystique, and if I wanted to be baffled by the spurious relationships governing a sequence of claims then I could listen to a politician on the radio. Personally speaking, I find nothing intrinsically admirable, interesting, or meaningful about other people’s dreams; from the fact that Morgan Harlow has included five poems that explicitly engage with dreams in a collection of fifty four poems (not counting those which don’t contain the word ‘dream’ but are nonetheless unavoidably dreamlike), I think I can say safely that this is an opinion not shared by the poet. The title bears no apparent relation to the poem: I can’t say whether gorillas dream, but I’m certain that they wouldn’t dream sophisticated puns on T.S. Eliot. The poem simply stops when it reaches its end, leaving the reader none the wiser about anything at all – least of all why they should carry on reading. Why should we care that ‘A– worried over the last survivors’? Why should we wonder what it is that they survived?

Despite my reservations and aversions, something about this collection has made itself at home in the back of my skull.

Looking back over what I’ve written, I feel utterly and unjustly curmudgeonly. I’ve overlooked something vital. Performing surgery on T.S. Eliot with Michelangelo’s chisel in a university humanities department is a gloriously striking image, and one with tremendous sticking power - and it’s delivered with an inspired inversion of ‘Prufrock’’s first line off the back of a line with an allusive range that spans The Godfather and Homer’s Iliad without overreaching. Something about the arrangement of parts makes this poem quietly gather attention. As a machine for remembering itself, ‘Gorilla Dreams’ is a success. Make no mistake: when Harlow’s poems work, they can be stunning. Whether capturing both sides of a relationship in ‘Hera and Zeus’ or charting the obscure pathology of an academic career in ‘A Bend in the Light’, she sketches motivation with a light touch many poets ought to envy. Her language is unencumbered by ostentation, working to a distinct rhythm all its own; where Harlow uses line breaks, she places them delicately and deliberately. And there’s an admirable compactness to much of her work that is neither miserly no arrogant; it imbues the collection with a mature, confident reserve, leaving the reader with the sense that they have been told precisely what the poet wishes them to know – no more, no less.

The best of the collection – ‘Hera and Zeus’, ‘A Bend in the Light’, ‘The Woman Who Lived Under the Hill’ – would turn my head in any collection: they’re simply very good. The same cannot be said for every poem in Midwest Ritual Burning. Some are simply dull. Though I am happy to admit that a verdict of dullness by a reviewer generally indicates a deficiency of either taste or sympathy, I am, on this occasion, willing to stick my neck out. ‘A Partial Lexicon: “Fresh” and Related’ is a pseudo-academic investigation of ‘Cattish’ loan-words. While it might well be effective as a performance piece, on the page it is humourless, graceless, pretentious and infantile. As satire, it might have a place recast as a piece of throwaway prose, or as part of a sketch review; as a poem, it must surely make the late Michael Donaghy spin in his grave. Other people’s cats, like other people’s dreams, are not a priori fascinating subjects for poems.

Picking on particularly weak poems is not particularly edifying, but ‘A Partial Lexicon’ provides a clear example of a flaw that bedevils Midwest Ritual Burning and threatens to undermine the collection as a whole. Interiority by no means spells doom for a poem, but in Harlow’s poetry it is often alienating and self-limiting. With the exception of ‘Eclogue’, her nature poems are purely descriptive in a way that precludes judgement. Her four poems responding to works by Joan Miro, though undeniably powerful and affecting, are nonetheless records of an unknown individual’s reaction to a stimulus the majority of Harlow’s readers will be unfamiliar with and will need to research, and which is, in any case, somewhat obtuse. While there is some ekphrastic content, Harlow’s concision prevents her from deepening the relationship between stimulus and percipient. The sense of development that gives her strongest poems such weight is entirely absent here, leaving little to which the reader may cleave: Harlow seems simply to present a view, but doesn’t show much inclination towards justifying this interest to her readers. Similar criticisms can be levelled at those poems which ventriloquise or engage with famous figures, real or fictional – though here Harlow manifests a quiet wit, rutting Walt Whitman into Nancy Drew and slyly outdoing an overused trope in ‘Lancelot meets Goya meets Cortázar meets Mowat’.

Try as I might, I struggle with these poems. Where they are referential, they privilege specific experience to exclude the uninitiated (as in the case of the cat that behaves "in the manner of Fellini’s/ Guido riding the back of a whore in 8½" in ‘On Halloween’); when they’re more observational, their contents are so underdetermined that the reader has no other option than to placidly accept what they are told. I found Norbert Hirschhorn’s close reading of the title poem instructive, but while he glosses over the risks of writing in fragments, I found myself returning again and again to how atomised Midwest Ritual Burning feels as a collection. Just as the scraps comprising Harlow’s ‘Journal’ poems barely hang together, the poems that comprise the collection stand with one another awkwardly, like strangers gathered in a doctor’s waiting room.

Again, though, I find myself vacillating, as if Midwest Ritual Burning is chastising me for being too reductive. The collection’s last poem, ‘Nursery Rhymes’, warns against glib readings and the literary tunnel vision they engender. In some ways it’s a curious note on which to close the book, with a claim that "Goldilocks and the Three Bears [is] about/ leaving your family and never going back", but at least here, finally, Harlow engages with herself in a way that I can understand and appreciate, balancing Midwest Ritual Burning between two poems that exhort the reader in different ways to distrust easy meaning and clear-cut comprehension. There’s the world, and there are our inconclusive attempts to make sense of it, and we can understand neither. Perhaps we’ll have to be content with that.

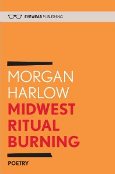

I feel compelled to add a postscript. Midwest Ritual Burning is one of the first collections put out by Eyewear Books, and its design deserves a little attention. Along with Eyewear’s other collections (Richard Lambert’s Night Journey, reviewed by my colleague Harry Giles; Kate Noakes’ Cape Town; Simon Jarvis’ Eighteen Poems; and Elspeth Smith’s deliciously titled Dangerous Cakes), its front cover is a bold block of colour, with the title and author joined by a few artfully positioned lines. The visual identity is very strong, and strikes a good balance between complicated, risky pictorial covers and the typographic minimalism of Smith/Doorstop’s pamphlets or Faber & Faber’s simpler offerings; Midwest Ritual Burning is a rich orange, with detail in black, white, and red, with red endpapers to match. The back cover, unusually, is mostly given over to a generous author photograph, with the blurb confined to a small textbox. The design of the book’s actual text, however, is slightly less cohesive, switching from the handsome sans serif font used for text on the cover to a more conservative serif font for the colophon, then back for the web address on the same page, then into sans serif for the author bio, then back to a serif font for the contents page. I mention this only because it’s such a strange choice in an otherwise impressively-designed book, and I can think of no sensible reason for it. It’s a small nitpick, but it niggles nonetheless.