reviewed by David Clarke

The silence that comes after is also the critic's silence

Kevin Powers’ Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting presents the reviewer, if not the reader also, with a significant challenge. Not that the poetry itself is difficult in formal terms: In fact, the language is easy to follow, the ideas are developed logically, the sense of the poems is carefully conveyed. The challenge of this poetry is not so much how to interpret it, but rather if one can interpret it, assuming that the possibility of interpretation is also the possibility of many interpretations, that is to say of the reader (or reviewer!) having room to develop their own relationship with poems without being pressed into a particular point of view.

Is critical analysis really in order? Doesn’t it feel somehow indecent?

Powers writes about the conflict in Iraq from the perspective of a former US soldier who served there, and the poems themselves are a testament to the post-war suffering that the ‘I’ of the collection (implicitly Powers himself) undergoes. These are poems of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), with all of its auditory flashbacks, ‘flat affect’ (as in the title of the poem ‘Valentine with Flat Affect’) and sudden bursts of anxiety (as in the poem ‘Separation’). The poems also reflect on the writer’s home, which he sees from his post-war perspective as, in its own way, riven with historical violence.

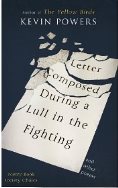

Powers’ previous book was a novel, The Yellow Birds, which was well received, and deservedly so. The poet, however, seems keen to assert a distance from this fiction, which describes the combat experience in Iraq, from the testament contained in his verse. In the collection’s title poem, we meet the Private Bartle of the earlier prose narrative, who is thereby clearly distinguished from the first person of Letter Composed During a Lull in the Fighting. This gesture to autobiographical authenticity is implied formally as well: the irregular stanzas, the varied and often clipped line lengths, and the confessional tone of the poems frequently put me in my mind of Robert Lowell’s Life Studies, perhaps most clearly in those poems which deal with Powers’ childhood in West Virginia. Powers’ verse, although clearly crafted, wants to appear rough-hewn, spontaneous and responsive to raw emotions, so that it is rarely neat in formal terms.

All of this contributes to the difficulty this book presents to me as a reviewer. The very authenticity, or at least the staged authenticity, of the poems and the horrific experience out of which they emerge seriously call into question the function of criticism. Presented as an expression of deep anguish, however artfully conveyed, what else can one do but acknowledge that anguish and offer empathy. Is critical analysis really in order? Doesn’t it feel somehow indecent? This is not a new dilemma, of course. As Elisabeth V. Spelman relates, in the 1980s, the eminent New York dance critic Arlene Croce once refused to even watch a performance staged with AIDS patients on the grounds that, in the face of such agony, the critic’s function became redundant. All one could do was feel sorry for those involved. In the case of Powers’ poems, I feel a similar desire to retreat in the face of a suffering which, implicitly, cannot be argued with. However, on reflection, that feeling is not just a product of the subject matter here, but also has something to do with the way that the subject matter is conveyed.

The Yellow Birds is, in my view, a significant novel. Through his fictional protagonist, Powers is able to convey a real sense of the moral complexity of modern warfare. He is unsparing with his characters. They are portrayed as joining the military to prove themselves as men, but then abdicate their responsibility for making moral choices to that institution; the opposite of mature self-determination. As the narrator of the novel says: ‘It had dawned on me that I’d never have to make a decision again. That seemed freeing, but it gnawed at some part of me even then. I had to learn that freedom is not the same thing as absence of accountability.’ The Yellow Birds explores this moral paradox of military life – of being at once subjected to the will of others through military discipline, yet unable to fully shake off the moral burden of the violence committed and witnessed – in such a way as to leave the reader shaken and appalled, but at the same time unable themselves to take any easy moral position of condemnation. It is a book that asks about all of our complicity in such violence in a way that I think is truly important. This kind of meditation on the nature of violence and morality is certainly possible in poetry: Brian Turner’s work and, more recently, Dan O’Brien’s excellent War Reporter are good contemporary examples of this. I am sad to say, however, that – for me at least – Powers’ poetry fails where his novel succeeds so dramatically.

This failing comes down to perspective, most starkly in the poem ‘Improvised Explosive Device’, one of the longer ones in the collection. It begins as follows:

If this poem had wires coming out of it, you would not read it. If the words in this poem were made of metal, if you could see the mechanics of their curvature, you would hope they would stay covered by whatever paper rested in the trash pile they were hidden in.

The reader is compelled here to share the soldier’s fearful situation, and the sense of ever-present danger is conveyed persuasively. Powers is skilful in his choice of an everyday setting (a pile of rubbish) to give the reader a sense of how war uncannily transforms what would otherwise be harmless into something potentially deadly. It reminds me of a great-uncle of mine who fought in Italy and always recalled the orchards of fruit he saw, but was afraid to touch in case the retreating German army had booby-trapped them. As the poem progresses, however, the poet narrows the perspective to that of the soldier who, under this stress, shoots a civilian he sees talking on his mobile phone, which may or may not have been the trigger device for a bomb that has wounded one of the soldier’s comrades.

If this poem had fragments of metal coming out of it, if these words were your best friend’s leg, dangling, you might not care or even wonder whether or not it was the man’s mother on the other end of the telephone line. For one thing, it would be exonerating. Secondly, emasculating (in the metaphorical sense of male powerlessness, notwithstanding the likelihood that the mess the metal made of your friend’s legs and trousers has left more than that detached). If this poem had wires for words, you would want someone to pay.

The poet-soldier’s feelings of wanting ‘someone to pay’ are not presented as those we might share, but rather as those we must share. There is no room for us to critically assess them. We too, so the implication, would react in the same way: we would also shoot the (possibly innocent) civilian. Just as the soldier is presented as having no choice, so we as readers are offered no choice as to how we might react in this situation.

Elsewhere, the violence perpetrated, over which the ‘I’ seems to have little control, is filtered only through his own distress, the suffering of others taking on significance for the most part where it impinges on his own emotions: ‘I appreciate the fact / that for at least one day I don’t have to decide / between dying and shooting a little boy.’ This disconnect from the suffering of others is doubtless a symptom of war and perhaps also of PTSD, and there is consequently a truth in the situation Powers describes here. However – unlike in his novel – he is unable to find a place for any consideration of the suffering of others and his part in it; nor will he allow the reader the space to explore that relationship. This is particularly apparent in a poem like ‘Photographing the Suddenly Dead’, where the subject has hidden a photograph of three young Iraqis killed by his unit in the bottom of a duffle bag. The Iraqis themselves earn only the briefest of mentions in this long poem, and the photographic image of their dead bodies stands primarily for the trauma experienced by the American soldier, who is unable to forget participating in the violent killing of probably innocent Iraqis. Again, there is clearly a truth to this situation, and a very unpleasant one at that, but I was still left with the uneasy feeling that the Iraqis in this account are merely the occasion for the more horrific and somehow more interesting suffering which is happening to the former soldier.

The poems remain resolutely focused on the combatant’s wounded psyche and his attempt to hang on to a coherent sense of self. In ‘Independence Day’, this preoccupation becomes almost comic. The device of breaking a line almost every time the pronoun ‘I’ is used, so that an uneven column of them stands out along the jagged right-hand margin of the poem, expresses this self-obsession, but almost to the point of (unintentional?) parody. Even when looking back at the darker aspects of his home-town background, in poems like ‘The Locks of the James’ and ‘Church Hill’, the poet admits that ‘mine is the only history / that really interests me’, while at the same time refusing to take on the burden of that history (‘No one should be blamed for this.’) However, those who did not go to war are blamed for their lack of a sense of responsibility for what has happened to the soldier, although not ever for what has happened to Iraqis. For instance, we see a gang of ‘Young Republicans / in pink popped collar shirts’ in the poem ‘Separation’, who laugh and drink while the former soldier ‘screamed / and wept and begged’ for the rifle he has had to give up and which is the only thing he has faith in to protect him. A fair target, perhaps, if an easy one: but again the other people who appear in the book are chiefly of interest for their relationship to the poet’s own suffering.

In this sense, I found this a claustrophobic work. Arguably, it puts the traumatised self on show, a self which cannot help but interpret the world around it in relation to its own wounds and which cannot see beyond those wounds to understand others and their suffering as existing in their own right. That may, of course, be valuable as an exercise, but it is an exercise which lacks the moral depth of Powers’ earlier novel, and consequently fails to move, even when demanding our empathy.

This is not to say that the book does not contain some good individual poems. When the voice of the poet achieves some distance to the subject matter, when it is not trying to say too much and manoeuvre the reader into agreement with it, then Powers’ work does achieve an understated force: I’m thinking here particularly of poems like ‘Meditation on a Main Supply Route’ or the wonderful prose poem ‘Fighting out of West Virginia’, which is all the better for finding an oblique relationship between its anti-heroic subject and the poet’s own war experience.

However, there is also a tendency to want to force the poems onto some higher philosophical plane in a number of cases, often signalled by an opening which makes a broad statement, for instance ‘History isn’t over in spite of our desire / for it to be’ (‘The Locks of St James’). Poems frequently end in a similar fashion, without the reader necessarily having the sense that a sufficient distance has been travelled to merit such declarations (e.g. ‘Order is a myth’ in the final line of the poem ‘Nominally’). Nevertheless, Powers at times shows a talent for a good ending: ‘You came home / with nothing and you still / have most of it left.’ (‘After Leaving McGuire Veterans Hospital for the Last Time’). His line-breaks are considered and often surprising, but he also sometimes falls into the trap of trying to turn prose into poetry through lineation alone:

A complete picture of the universe as it currently exists is not impossible, only difficult. (‘A Lamp in Place of the Sun’)

I don’t doubt that this book will do well (in the UK it will be a PBS Summer Choice this year) and reach a wide audience, not only because of its subject matter, but because of the deserved reputation of Powers’ novel. However, I have to say that I remained unconvinced. The poet’s experience demands empathy, and his poetry demands it too. However, the formulation of that demand was not one I felt I could respond to. Or, to be more precise, I felt that the empathy I was called upon to offer tended to block out the view of a more complex moral terrain that Powers has yet to explore in his poetry.