reviewed by Rowyda Amin

Coming in, coming out, and the darkness inbetween: Idra Novey on the American prison system.

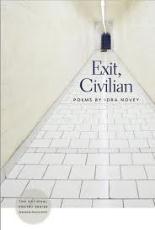

Exit, Civilian, which was selected for the National Poetry Series by Patricia Smith, takes prisons as its subject matter. Novey taught for several years in a women’s prison as part of the Bard Prison Initiative and this experience has become an avenue for exploring incarceration and its effect on the individual and society. The lived condition of prisoners is lyrically and minutely drawn, as well as the experience of the visitor entering the prison world. Novey stretches beyond depictions of inmates’ lives to explore the relationship of the prison, as edifice and as idea, to the wider community, the ‘electoral world’ beyond its walls whose changing purposes it serves.

Novey’s poems and the questions they raise are timely and crucial in asking her compatriots to consider what the state of their prisons says about them.

The reasons why an American poet might consider prisons to be a topic worthy of an entire book are not hard to identify. The USA has the highest documented incarceration rate of any country, with nearly 1% of the population behind bars. Novey’s poems ask what place prisons have in the social and moral landscape of the country and in its collective imagination. The narrator of ‘Riding by on a Sunday’ cycles past a prison and is prompted to debate her own relationship to the brick building: ‘I tell myself prisons are inevitable and inevitably awful. / Tell myself this thought is just another way of looking away.’ There is a similar sense of unease in ‘Civilian Exiting the Facilities’, in which the narrator wonders what kind of crime she might be capable of: ‘Would I have to be hungry. Could it happen over nothing. Could it happen nightly.’ Novey draws attention to the fact that the dividing line between the free and the incarcerated is more ambiguous than it might seem. In ‘Aspect’, the narrator acknowledges her mother’s imprisonment and the shame and silence surrounding it:

About the night my mother spent in jail, we say nothing: once my grandmother said imagine, your pantyhose stripped in a hallway.

Novey has said in an interview that she ‘can’t imagine writing without taking into account the world around [her]’. She is engaged with other artists too – there are poems in this collection after Vasko Popa, Louise Bourgeois and Mahmoud Darwish, as well as titles borrowed from Brazilian writers Graciliano Ramos and Clarice Lispector. Exit, Civilian opens with the sequence ‘The Little Prison’, a response to Vasko Popa’s series ‘The Little Box’. The disarming title is undercut by the details contained in the poems. Popa’s restrained, elliptical surrealism is channelled by Novey in short lyrics that describe the prison in terms which evoke the Panopticon that Jeremy Bentham described as a ‘mode of obtaining power of mind over mind’:

The little prison Has no interest in silence If you crack a door It beeps back at you If you try to read The Speaker will tell you Who’s collecting garbage And who’s expected on the second floor

The intrusion of the disembodied, nameless Speaker precludes mental retreat or silent reverie, demonstrating that the prisoner’s mind is as regulated as her body. Although the prisoners are subject to constant surveillance and intrusion, Novey draws attention to the fact that they are simultaneously hidden from the outside world: ‘The wet breath / Of its red bricks / Is all the world hears / From the outside.’ The prison, as Novey depicts it, is a liminal space, and the convict entering the system leaves a changed person. This change, essentially a diminution, is described through a series of metaphors:

Enter the little prison a comma And you come out a question mark Enter a scallop And you come out the shell Enter in English And you come out murmuring What your great-grandmother murmured To other shells On another shore Enter an apple And come out the teeth marks In its yellow core

The transformation wrought by the prison has a wider effect in the case of Novey’s poems about two South American ex-penitentiaries. The poems ‘O Caldeirão do Diabo’ and ‘Memórias do Cárcere’ are concerned with the Candido Mendes prison in Brazil, which was used during the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas to house political prisoners. The narrator asks local people about the prison and gets either no response or inconsistent stories. Nature and human forgetfulness efface what remains: ‘Enough lushness to erase everything / that’s not green or dengue fever, / mosquito or sky’. In ‘The Ex- Cárcel of Valparaíso’, the narrator is disconcerted at the repurposing of a disused prison in Chile as a place of recreation. Musicians tune their instruments in empty cells and children play in the prison, ‘children… who would in time build a prison of their own, and maybe empty it, maybe fill it again.’ This forgetfulness seems dangerous, part of a dysfunctional cycle that will feed more people into not-yet-existent prisons.

It is noteworthy that Novey never ventriloquises the prisoners. The narrative voice in these poems is largely that of the interested outsider, except in poems written in the persona of the prison itself. Novey’s depiction of prisons is disconcerting, but never strident or predictable, although ‘Riot’ stands out for broaching the comparatively predictable topics of overcrowding and inadequate facilities. Ultimately, the prison remains inscrutable in these poems. A repository for those we fear, a shameful necessity. Dostoyevsky wrote that ‘the degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.’ With the USA sending so many of its citizens to prison, Novey’s poems and the questions they raise are timely and crucial in asking her compatriots to consider what the state of their prisons says about them.