A broadside of ekphrastic, observational and conceit-driven poems which achieve a mood of uncontrived innocence, coupled with a knack for plain-but-memorable phrasing.

One of the characteristics of contemporary poetry that infuriates those who possess only a passing familiarity with it is its lack of moralism. We share somewhat rigid expectations of art; if it isn’t funny, violent or voyeuristic then it should at least have an opinion, be For or Against. But poetry resists, preferring to explore subject matter nonjudgmentally and without definitive pronouncements. In the case of Andrew Pidoux, this is one of his most striking qualities.

Pidoux brings a sense of impartial enquiry to an array of subjects, most notably and most keenly the figures in various paintings.

For proof of this, one needs look no further than ‘Entrepreneurs’, which cycles through Branson, Baezos, Jobs and Trump without a glimmer of pro or anti sentiment, even when a word as dirty as ‘money’ is used:

Richard Branson is an entrepreneur.

He sails around the world

In giant silver tears

That fall to earth too soon

And drape themselves on the sea.

He has his fingers in money pies.

What could, in contexts outside of art, be derided as a kind of moral cowardice comes across with such careful poise as to be subversive, Pidoux refusing to join in the opinionated squawking that afflicts our engagement with any hot topic. And if moguls ultimately deserve to be condemned for their habits of exploitation, the real triumph of this resistance is apparent in poems like ‘The Cove Dweller’, where the same simple human courtesy is extended to the emotionally vulnerable would-be novelist working away in Starbucks, whose aspiriations and self-absorption could be so easily mocked:

The way she leans into the keyboard

As if listening to it, and the way her fingers

Splash with such delight ...

Pidoux brings the same sense of impartial enquiry to an array of subjects, most notably and most keenly the figures in various paintings, whose secrets and whose emotional journeys he reconstructs with keen empathy and a comic imagination. He’s equally deft when introducing anachronisms (one of Picasso’s three musicians plans on starting a blog) or evoking wretchedness, as in his response to Rousseau’s ‘Carnival Evening’:

But they seem too stiff to either stand

or fall. Uneducated in the laws

of their own composition,

they simply hang together,

and love each other sadly

from the corners of their eyes.

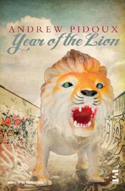

That same inclination allows him to veer between eulogising the dead and teasing out oddball narratives, or switch from free verse to formal constraint, all the while retaining a subtly distinctive voice. There’s no question, for instance, that it’s the same poet writing the title poem (a winning slice of science fiction, reminiscent of Fleur Adcock’s ‘Gas’, in which the mass-manufacturing of lion cubs as Christmas toys precedes a grisly massacre – a fable with its moral left unstated) and the final piece in the book, an oddly brittle sequence of pop song imaginings:

If I were the world,

So round and sweet and ripe,

I’d put my feet up on the sun

And smoke a comet pipe.

In addition, he’s very capable with metaphor and simile; “rockeries of gifts” lie beneath Christmas trees, a librarian's fingers “flutter to find / a beach of words to comb”, new songs are found “coiled sleepily / In the guitar's belly” and a lost crab moves “like a living army of bones”, to name a few. One or two ring false, and sometimes his whimsy is a little too sweet, but otherwise, the basic good-naturedness of these poems is genuinely heartening.

Pidoux took a long break from both poetry and Britain after winning his Eric Gregory award in 1999 (the same year as Matthew Hollis, now an editor of Faber). He should be welcomed back.

Dr F sez: In ‘Levitation’, Pidoux describes a man who can “lift children / By the head, so it didn't hurt them”, returning them to the ground with “a new lightness”. I think it's fair to say that Pidoux has achieved, through these poems, a similar effect on the above reviewer. But I, Dr Fulminare, am too tall and towering to be lifted by the head! I seek answers in the form of literary formulae, and Pidoux refuses to give them – except, that is, when he uses his lyrical gifts to bring to life the figures in works of art. This work I can well appreciate.